Despite only selling one painting in his lifetime, to a (perhaps sympathetic) relative, Van Gogh became an absolute cornerstone in the history of Western culture. His thick, fluid brushwork and vibrancy of colour revolutionised the art world, bold and daring and inspirational to thousands of artists, acclaimed or amateur. A later realised struggle with depression extended his influence further than the parameters of the art world. It has been explored as the romanticised image of melancholia in Don McLean’s 1971 song Vincent and a recent episode of Brit classic Doctor Who as well as importantly shed light on discussions looking into the societal prevalence of mental health issues.

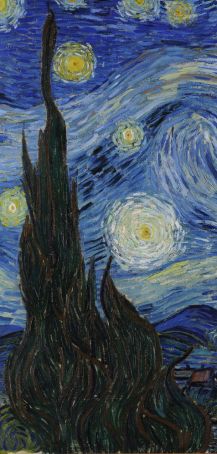

Prints of Starry Night have appeared worldwide on umbrellas, clothing and crockery, whilst millions of visitors still flock to MoMA every year for a glimpse of the original painting. It is, undoubtedly, one of the most recognisable paintings of all time.

This is precisely why I see it as a great place to begin this blog’s discussion of art. Its popularity, content and aesthetic, I feel, serve brilliantly to introduce various discourses on art history and the multitude of ways art can be interpreted.

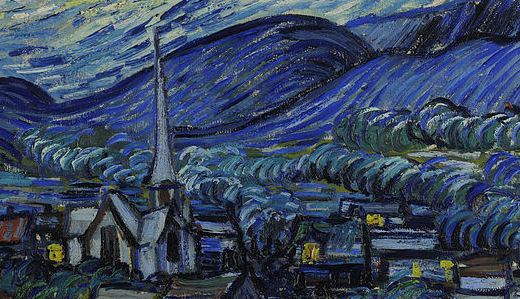

An obvious point to begin (although shockingly often overlooked) is just the painting. What on earth are we looking at here? Instantly we are captured by the expanse of twirling night sky, pocketed with intensely bright stars swimming in orbs of their own luminescence. There is a village nestled beneath rolling hills in the middle ground of the picture, from which a spire pokes upwards and tiny speckled lights wink at the viewer. In the foreground a magnificent collection of cypress trees flows in the wind and challenges the village spire’s height. At face value it doesn’t seem like a complex painting at all: nothing more than a night-time view of the country.

But, as soon as we make these assertions they are unravelled by the brilliance of Van Gogh’s depiction. Arguably the actual content of the painting is not the physical things included but the way in which they have been painted. Stylised brushstrokes form patterns on the canvas, like merging waves, giving the surreal impression that land, sky, and all other matter in the scene are made of the same fluid substance. Paradoxical, unearthly lighting – apparently night but possibly day – and viscously monstrous cypress trees couple with this material quality and strike the viewer as unsettling, unresolved abnormalities. This is of course only one interpretation. Often the spirals and vibrant cooling colours affect viewers with a sense of comfort and ease. The quiet, cosy village in the valley might remind people of childhood or conjure dreams of an idyllic escape to the country.

From these responses we begin to interpret reasons for Starry Night looking the way it does. We begin to ask why would Van Gogh paint this as he has. Can we see hints of frustration and unease in the spiralling movements? Or does the complementary lighting invoke sentiments of relaxation and mindfulness? Personally, when I look at this painting I feel a sense of trepidation mingling with nostalgia, the overwhelming blue palette instilling a peculiar peaceful sorrow.

Now, I could say that the reason for this is because Van Gogh himself was a sad, troubled man. I could say the cypress trees, with their connotations of death and mourning, and the sporadic brushstrokes emphasise this restlessness. I could say this idea is supported by the fact that this was painted from an asylum window. But this would be a far-fetched approach. The behaviour demonstrated on the canvas may not correspond so neatly with Van Gogh’s persona. It does not necessarily take someone who is joyful to write a joyful song, nor someone sad to paint something sad. It is very much a retrospective reading to claim qualities of a painting as articulations of personality. Van Gogh wrote very sparingly about his work and may not have intended for any such interpretations, perhaps only wanting to paint a pleasant scene.

What then becomes tricky with looking at art is that this reasoning does not diminish secondary interpretations from the viewer. How we react to art is always valid because that reaction is personal and subjective. The feelings I take from Starry Night are perhaps governed by my own sense of self, not just the painting. What is not valid is when we claim our interpretations are the exact and only purpose of the work. Something emotive is coming to life from this image (after all art is an expression!) but it is multifaceted and not easily determined.

This brings me to a question I intended to set out with in looking at Starry Night: if we cannot explain the image, why does it command so much popularity in our society? The troubled artist-philosopher caricature has proved enticing in Western culture – think Hemingway and Pollock – but that cannot possibly explain this painting’s fame. Aesthetically it is certainly pleasing. Exciting, modern, colourful, yet still easy to comprehend, the response to Van Gogh’s work is generally positive. Certainly more so than works of further abstraction. Is it maybe just the name? Van Gogh is definitely a household icon, so perhaps this is why people continue to be fascinated.

All these questions, about society, the mind, expression, value and a thousand other things that have not been covered here, spring from the experience of looking at art. To me, the root of value lies in the fact that there is no solid answer. If this could be easily explained there would not be as much a need to talk about it. Starry Night mystifies viewers in its initial obviousness but perpetual ambiguity. Like all art, there are no real answers. There are only prompts for discussion.

This is a wonderful walk-through of one of my favourite paintings. Thank-you 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person