With their blend of bold realism and soft fantasy, the Pre-Raphaelite paintings are some of the most popular in the world today. Inspired by art critic John Ruskin who called for artists to take nature as their source, the Brotherhood of seven friends ditched Royal Academy demands and shook up their stagnant art world with a renewed spirit of medieval mysticism. To keynote artists promoting this resurgence of early Italian simplicity – like John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti – the female face became essential.

As a critical point of artistic reference, painting women was an easy route for these artists to deviate from and show off their spectacular creativity. Instead of portraying the systematic disproportions, peachy marble skin, and lacklustre gazes common among classical Venuses, the Pre Raphaelites committed to capturing likenesses of real women. Framed in gold, their fierce females modelled on Elizabeth Siddal, Jane Morris and the others with strong-jaws and sharp-eyes still captivate us just as unforgivingly as when they first stormed the scene in 19th Century Britain. Accusingly melancholic and devastatingly stunning, these women play on our art-loving consciousness as graciously as the lull of any cherished fairytale.

Yet, although art history repeatedly reminds us of how these real life beauties were transported into Arthurian legend or ancient myth, did the Pre-Raphaelites release a modern woman or actually perpetuate gender norms? Provocatively tiptoeing the line between empowered woman and contained female, these paintings have spurred debate among feminist art historians and even the most novice museumgoers since the 1970s. As a question of identity and representation, so much is always open to be explored.

Rossetti’s Angels

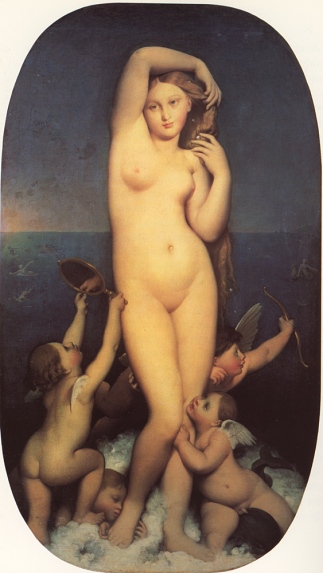

None of the artists painted women with as quite as much zeal as Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The aesthetic associated with Pre-Raphaelite movement, rejected in the late-1800s and that still often viewed as unconventional beauty, stems primarily from his work. By deliberately representing real women in the guise of ancient, medieval, and Shakespearean heroines, he awarded the characters an iconic element of enigma unachieved by the earlier Western canon. In his paintings, the unearthly is brought close to home, swaying between what is real and what is imagined. They mesmerise to this day, whilst conventional pieces like Ingres’ Venus remain distant in a celestial tower, bland by comparison.

Over the course of his career, Rossetti employed a number of models with strikingly similar appearances. In his many drawings of Elizabeth Siddal (wife and early model whose face became the infamous drowned Ophelia by Millais) we see a preference for sharpness rather than soft features, especially in the arch of her eyebrows, nose, and curved lips. It’s obvious Siddal inspired Rossetti for being atypical of convention, however there is something unsettling about his relentless repetition of such piercing features and swan-like necks. It seems Rossetti was not wholly set on capturing the unique qualities of each woman’s face, but instead Siddal served as muse and the artist refined his choices of model to meet a personal ‘type’ of beauty. By the time he painted Jane Morris, despite successfully capturing likeness, the look is so exaggerated that her lips resemble bruises, her eyes are hauntingly glossy and her neck so long it stretches out as if waiting for the chop. Forthright representation is exposed as an indulgence in desired qualities of the real life women.

When we learn about the relationships Rossetti had with the women he painted, the weight of unease becomes all the more heavy. Ford Maddox Brown, a fellow Pre-Raphaelite, once commented on Rossetti’s “monomania” for Siddal’s appearance. His sister Christina wrote in poem, “He feeds upon her face by day and night”, illustrating the obsessive fixation he had on her beauty. After Siddal’s dabbling in laudanum that led to addiction and death, Rossetti’s quest for similar features in women suggests an unhealthy infatuation that mounted to desperate searching for a substitute woman. The idiosyncrasies of each face can be seen melting into one insidious venture of a man tortured by the memory of his dead wife. The macabre tale of Rossetti’s lost lover is forever frozen in his painting Beata Beatrix (a scene from Dante Alighieri’s poem as the heroine takes her dying breath). In the painting, we can almost feel beauty slipping between the artist’s fingers as Siddal disappeared into the abyss.

Problems for feminism

Rossetti’s paintings, troubling as they are for distilling women to a preferred type, are not necessarily misogynistic. Posing as mythical figures, you could arguably rule the paintings have nothing to do with the real women and so it doesn’t matter that beauty was narrowed to fit Rossetti’s obsession. Art, after all, is an expression of the artist’s perspective.

One of the core motives of the Pre-Raphaelite movement does, however, cause difficulty for women. Following Ruskin, the artists took it upon themselves to use the messages art can convey as an opportunity to refresh the world’s moral compass and improve society. The problem? In such paintings, the point of social responsibility invariably falls upon women.

William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience is a classic example this dilemma. Trying to instruct Victorian viewers against having affairs for the sake of their inner morality, Hunt presents us with a scene of two illicit lovers. An uncouth gentleman has whisked away his mistress (notice the lack of wedding ring) to a private house for their meetings, but she has a sudden spiritual awakening. Struck by the light falling through a window behind us, the woman pushes away from the man, realising the wrongdoings that lie in wait with him and instead she chooses the symbolised possibility of redemption. In the case of this painting, it is the woman’s duty to evade seduction and remain pure; the man is not so reprimanded for his destructive behaviour.

On the flipside, the Pre-Raphaelites are renowned for having obsessed over the femme fatale. Playing the part of temptress, this erotic but invulnerable woman represents the malevolence of courtly love gone wrong. Historically she has existed in legend as mermaids, sirens, or witches disguised by beauty, like Circe or Morgan Le Fae. She has caused contest between feminist interpretations because whilst in an active, powerful role, as the seductive bringer of men’s downfall she nevertheless is in a position of blame. Imprinted with the romanticised metaphor of tragedy or fatality, it is also argued that these women lose their identity and agency, becoming nothing more than decorative arrangements of sexualised bodies for male fantasy. Active or passive, it cannot be ignored that ‘woman’ is regularly depicted as the source of social dysfunctions.

Another uncomfortable issue with the Pre-Raphaelites is the attitude towards models themselves as they were placed in allegorical narratives to morally instruct viewers. In Rossetti’s Lady Lilith, the face of Fanny Cornforth who posed for the original was replaced half a decade later because subsequent model Alexa Wilding was considered to suit the narcissistic character better. Her hair is painted as more luscious and abundant, symbolising a poisonous sexual invitation that taps into femme fatale typecasting. In this respect, the models were chosen not simply for being suitably beautiful, but because of their physiognomy: a dangerous subjective code that deciphers the character of a person based solely on their appearance. Such symbolism directly plunged the real women into contemporary debates around expectation of the female persona. Efforts to value individual models are undermined and instead Victorian perspectives on women impact the artwork regardless.

It is clear that the romance and attention surrounding these women paradoxically diminished who they were as women. Stripped of their actual personas and given over to archetypes they were portraying, we can imagine many parallels with modern day actresses and models.

For this reason, interpretations that look at contemporary photographs of Morris and Siddal to praise the Pre-Raphaelites’ accurate representation are deeply flawed. Aiming to create variety and put distance between their work and convention does not mean the women were anymore valued for who they were as people. Jane Morris is remembered as one point in a love triangle rather than for her instrumental craft skills; Lizzie Siddal is ennobled for her near death whilst posing for Ophelia but her struggles with depression are dismissively forgotten. It is a lazy kind of feminism to perceive any action or inclusion of women as an action of feminism. Whilst better than prior idealisation, stopping here does not dig deep enough. Women are nevertheless rendered as types, dismembered from their identities, creatures of oppressive, Victorian symbolism.

How do we view them today?

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery currently houses the most extensive collection of the Brotherhood’s work in the world. Despite the issues raised above, we cannot deny their popularity among modern audiences.

What a lot of feminist criticism of the paintings boils down to is a need to dictate what defines ‘woman’ in the abstract sense. This, in many ways, disregards discussion of why people still adore these women. As fearsome heroines, their beauty and agency command absolute reverence. They are not merely served up for brief titillation. Shock, awe, and desire spill out all at once from the frames and this is something we should not be afraid to embrace. So many guilt-tripping questions are posed to modern women and always along a similar line: how can you be beautiful, nonchalant and sexually confident whilst also committed to goals, loving and respected? In truth such complexities are not even a little bit mutually exclusive and should not be viewed so. The Pre-Raphaelites avoid losing substance and continue to marvel viewers because the artists do not polarise their women. Women, they show, can be any combination of any character.

At the San Diego Comic Con 2015, the annual ‘Women Who Kick Ass’ panel invited actresses from popular cult TV to discuss what their characters mean to them. Natalie Dormer who plays Margaery Tyrell in Game of Thrones praised the show for creating women with multidimensional forms of power. Complex and contradictory, Margaery is by all means a femme fatale, compelling and potent, assertive and compassionate, surprising and inspiring. And, much like the Pre-Raphaelite women, she is loved for it.

The continued admiration for these paintings suggests a revision of feminism is needed; women should not be challenged over who they choose to be and show to the world. It is a backwards, Victorian idea that women have to define themselves as what kind of woman they are and have society decide if that’s appropriate or acceptable. To move forward, we need the Pre-Raphaelites, above all, to keep showing the world how barriers we thought were hardly there can always be broken through.

[…] https://speakingvisuals.wordpress.com/2016/07/19/a-dangerous-beauty-pre-raphaelite-women-and-their-l…; […]

LikeLike

Hi Lorna,

Would it please be possible to have your surname so that I can cite some of your comments regarding Pre-Raphaelite beauty for a third-year assignment I am currently writing?

Thanks,

Stephannie 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Stephannie,

Absolutely! My surname is King. Might I ask, what are you writing the assignment on? Hope it goes well.

Lorna

LikeLike

Thank you! Yes, I’m writing a source analysis on how Imperial advertising shaped gender roles and race relations in Victorian Britain. I’ve found some advertising companies who used and adapted Pre-Raphaelite artwork to use in their now-famous soap adverts.

Many Thanks,

Stephannie

LikeLike